Drug comes from the French word “drogue” which means “dry herb”. A drug is defined by U.S. law as any substance (other than a food or device) intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, relief, treatment, or prevention of disease or intended to affect the structure or function of the body1 . Drugs are foreign substances to the body but act by imitating endogenous compounds or substances like hormones and enzymes. Drugs interact with various systems of the body to produce a response. These interactions are complex and can vary depending on the type of drug and how it is administered. In the paragraphs that follow, the manner in which a response is generated, by a drug interacting with the body will be discussed using concepts of pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics and an example of a drug’s mechanism(diazepam) briefly illustrated.

Drug action not to be confused with drug mechanism is; the functional or anatomical changes at the cellular level resulting from the exposure of a living organism to a substance (drug) while drug mechanism refers to the specific biochemical interaction through which a drug produces its pharmacological effect2.

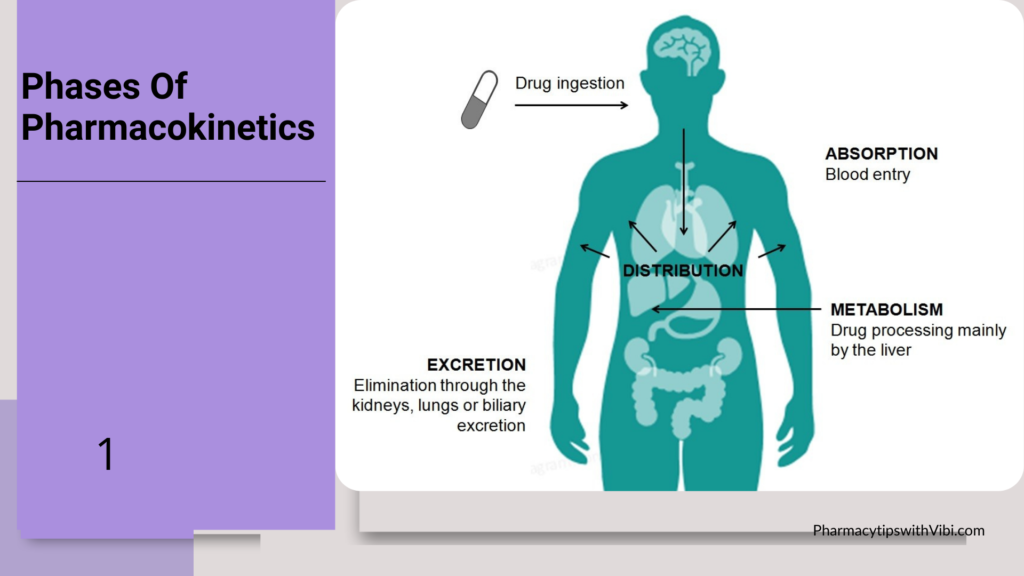

One of the key ways in which drugs interact in the body is through their absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. After a drug is ingested or administered, it must be absorbed into the bloodstream to reach its target site of action. The drug is then distributed throughout the body, where it may be metabolized by the liver or other organs. Finally, the drug is excreted from the body through urine, faeces, or sweat. This process, is known as pharmacokinetics.

Pharmacokinetics process plays a crucial role in getting the drug in the body to their target areas and also helps them to be eliminated to prevent toxicity which might lead to death. Hence determining how a drug (concentration) will interact with their sites to produce a response.

Once a drug has been absorbed and distributed in the body, it can interact with its target sites to produce a response.

Most drugs work in the body by either inhibiting enzymes or binding to; protein receptors, the genome or microtubules, membranes and fluid compartments.

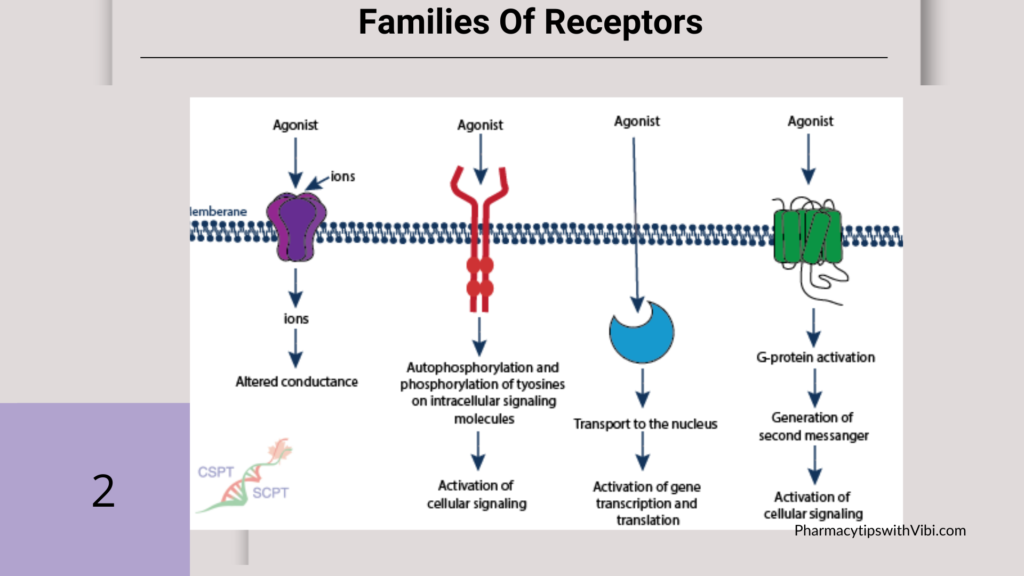

Receptors are macromolecules present on the surface of cells in the cytoplasm or in the nucleus with which the drug binds and interacts to produce cellular changes

Drugs can bind to specific receptors on cells, triggering a cascade of biochemical reactions (thanks to it having an affinity and intrinsic activity with the receptor) that ultimately lead to changes in cellular function.

Most drugs act by being either agonists or antagonists at receptors that respond to chemical messengers such as neurotransmitters. An agonist binds to the receptor and produces an effect within the cell. An antagonist may bind to the same receptor but does not produce a response, instead, it blocks that receptor to a natural agonist. A partial agonist can produce an effect within a cell that is not maximal and then block the receptor to a full agonist. Antagonism may be competitive and reversed by higher concentrations of agonists. Insurmountable antagonists bind strongly to the receptor and are not reversed by additional agonists.

Pharmacological receptors can be divided into four “superfamilies”: ligand-gated ion channels, G-protein-coupled receptors, direct enzyme-linked receptors, and intracellular receptors affecting gene transcription

Some drugs, their nature(agonist or antagonist) and their receptors; opioids such as morphine bind to opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord, leading to pain relief and sedation.

Salbutamol is a selective beta-2 adrenergic receptor agonist (bronchial and uterine). Nicotine is a muscle and neuronal nicotinic receptor agonist, Indicated in smoking cessation.

Ondasetron antagonist (to 5HT3 receptor for) selective synthesis indicated as an antiemetic.

Diazepam is a fast-acting, long-lasting benzodiazepine commonly used to treat anxiety disorders and alcohol detoxification, acute recurrent seizures, severe muscle spasms, and spasticity associated with neurologic disorders. In acute alcohol withdrawal, diazepam is useful for symptomatic relief of agitation, tremor, alcoholic hallucinosis, and acute delirium tremens.3

Its mechanism of action is as follows; Benzodiazepines exert their effects by facilitating the activity of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) at various sites. Specifically, benzodiazepines bind at an allosteric site at the interface between the alpha and gamma subunits on GABA-A receptor chloride ion channels. The allosteric binding of diazepam at the GABA-A receptor increases the frequency at which the chloride channel opens, leading to an increased conductance of chloride ions. This shift in charge leads to a hyperpolarization of the neuronal membrane and reduced neuronal excitability

Specifically, the allosteric binding within the limbic system leads to the anxiolytic effects seen with diazepam. Allosteric binding within the spinal cord and motor neurons is the primary mediator of the myorelaxant effects seen with diazepam. Mediation of the sedative, amnestic, and anticonvulsant effects of diazepam is through receptor binding within the cortex, thalamus, and cerebellum.4

Interactions come about due to reasons such as; Drug interactions occur on pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic levels. Examples of pharmacodynamic interactions are; the simultaneous administration of a NSAID and phenprocoumon (additive interaction), or of aspirin and ibuprofen (antagonistic interaction). Pharmacokinetic interactions occur at the levels of absorption (e.g., levothyroxine and neutralizing antacids), elimination (e.g., digoxin and macrolides), and metabolism, as in the competition for cytochrome P450 enzymes (e.g., SSRIs and certain beta-blockers)5.

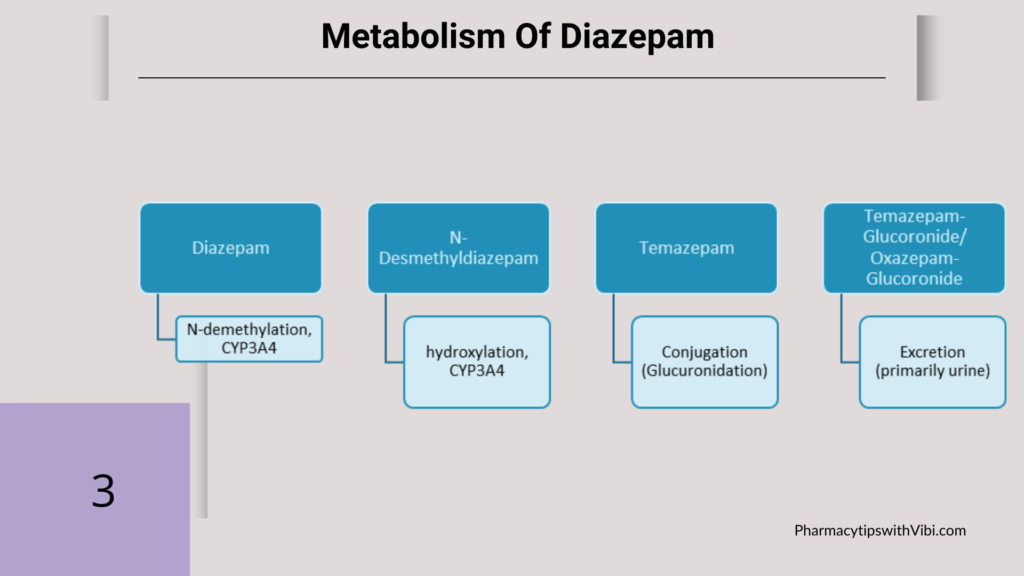

Diazepam is N-demethylated by CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 to the active metabolite N-desmethyldiazepam, and further hydroxylated by CYP3A4 to the active metabolite temazepam. Both N-desmethyldiazepam and temazepam are then metabolized to oxazepam. Temazepam and oxazepam are largely conjugated with glucuronide, and are excreted primarily in the urine.

Acute ethanol ingestion may potentiate the CNS effects of diazepam. Alcohol increases the absorption and raises the serum levels of diazepam. Tolerance may develop with chronic ethanol use. This is explained by decreased clearance of the diazepam because of CYP450 hepatic enzyme inhibition. The cognitive deficits induced by diazepam may be increased in patients who chronically consume large amounts of alcohol.

It is important for healthcare professionals to understand the effects of drug on the body and possible variations in theurapeutic outcomes.

The effects of a drug on the body are also influenced by factors such as dosage, route of administration, and individual variability. Higher doses of a drug may produce a stronger response but also increase the risk of side effects or toxicity.

The route of administration can affect how quickly and efficiently a drug is absorbed, with intravenous injection producing a rapid and intense effect compared to oral administration. Individual factors such as age, gender, genetics, and underlying health conditions can also impact how a drug is metabolized and its overall efficacy.

Healthcare professionals can prevent adverse reactions resulting from drug-drug interactions by:

Educating patients about the importance of adhering to prescribed dosages and reporting any adverse reactions can help prevent complications and ensure successful treatment outcomes. By staying vigilant and proactive in monitoring drug therapy, healthcare providers can help patients achieve optimal health and well-being.

Also, healthcare professionals should stay informed about the latest research and developments in pharmacology to provide the best possible care for their patients. With new drugs constantly being introduced to the market, understanding their mechanisms of action and potential interactions with other medications is essential.

In conclusion, drugs interact in complex ways with the human body to generate a response. Understanding how drugs are absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted is key to predicting their effects and minimizing potential risks.

By targeting specific receptors, altering neurotransmitter levels, and modulating cellular function, drugs can produce a wide range of therapeutic effects.

Bibliographic references

- Lynch, Shalini S. “Overview of Drugs.” MSD Manual Consumer Version, 12 Sept. 2022, www.msdmanuals.com/home/drugs/overview-of-drugs/overview-of-drugs.

- Spratto, G.R.; Woods, A.L. (2010). Delmar Nurse’s Drug Handbook. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4390-5616-5.

- Calcaterra NE, Barrow JC. Classics in chemical neuroscience: diazepam (valium). ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014 Apr 16;5(4):253-60.

- Friedman H, Greenblatt DJ, Peters GR, Metzler CM, Charlton MD, Harmatz JS, Antal EJ, Sanborn EC, Francom SF. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral diazepam: effect of dose, plasma concentration, and time. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992 Aug;52(2):139-50.

- Cascorbi I. Drug interactions–principles, examples and clinical consequences. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012 Aug;109(33-34):546-55; quiz 556. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0546. Epub 2012 Aug 20. PMID: 23152742; PMCID: PMC3444856.

- Dhaliwal JS, Rosani A, Saadabadi A. Diazepam. 2023 Aug 28. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 30725707.

- Friedman H, Greenblatt DJ, Peters GR, Metzler CM, Charlton MD, Harmatz JS, Antal EJ, Sanborn EC, Francom SF. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral diazepam: effect of dose, plasma concentration, and time. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992 Aug;52(2):139-50

- Barbara J Pleuvry,Receptors, agonists and antagonists, Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine, Volume 5, Issue 10, 2004, Pages 350-352, ISSN 1472-0299, (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1472029906003845)

- Page, S. W., & Maddison, J. E. (2008). Principles of clinical pharmacology. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 1–26). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-070202858-8.50003-8

- Nutt DJ, Malizia AL. New insights into the role of the GABA(A)-benzodiazepine receptor in psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2001 Nov;179:390-6.