Malaria significantly affects millions of people worldwide. Addressing this public health challenge requires understanding the impact of malaria parasites. Parasites transmitted through bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes cause malaria, a life-threatening disease that is preventable and curable. Five parasite species cause malaria in humans, with Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax posing the greatest threat (1). This essay will delve into the different types of malaria parasites, their life cycle, and how they are transmitted.

Malaria is an acute febrile illness caused by Plasmodium parasites, which are spread to people through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. It is preventable and curable. (2)

A mosquito infected by the parasite is not affected (nor does it die from malaria). This is because mosquitoes, unlike vertebrates, do not have red blood cells, their blood is a somewhat colourless fluid containing the blood cell equivalent called haemocytes. The parasites instead escape to the mosquito’s saliva from the gut (3).

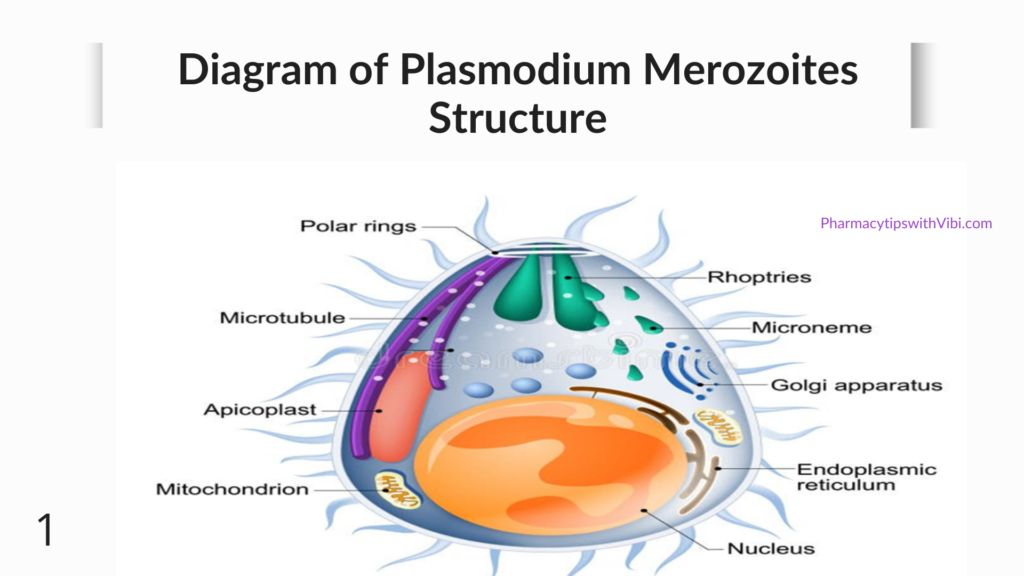

Plasmodium, a genus of parasitic protozoans of the sporozoan subclass Coccidia that are the causative organisms of malaria (4). The incubation period of the parasite varies from one specie to the other: 8 to 11 days for P. falciparum, 8 to 17 days for P. vivax. The 5 species of parasites that cause human malaria are; Plasmodium falciparum (or P. falciparum), Plasmodium malariae (or P. malariae), Plasmodium vivax (or P. vivax), Plasmodium ovale (or P. ovale), Plasmodium knowlesi (or P. knowlesi).

Plasmodium falciparum is potentially life-threatening. Patients with severe falciparum malaria may develop liver and kidney failure, convulsions, and coma. Although occasionally severe, infections with P. vivax and P. ovale generally cause less serious illness, but the parasites can remain dormant in the liver for many months, causing a reappearance of symptoms months or even years later (5).

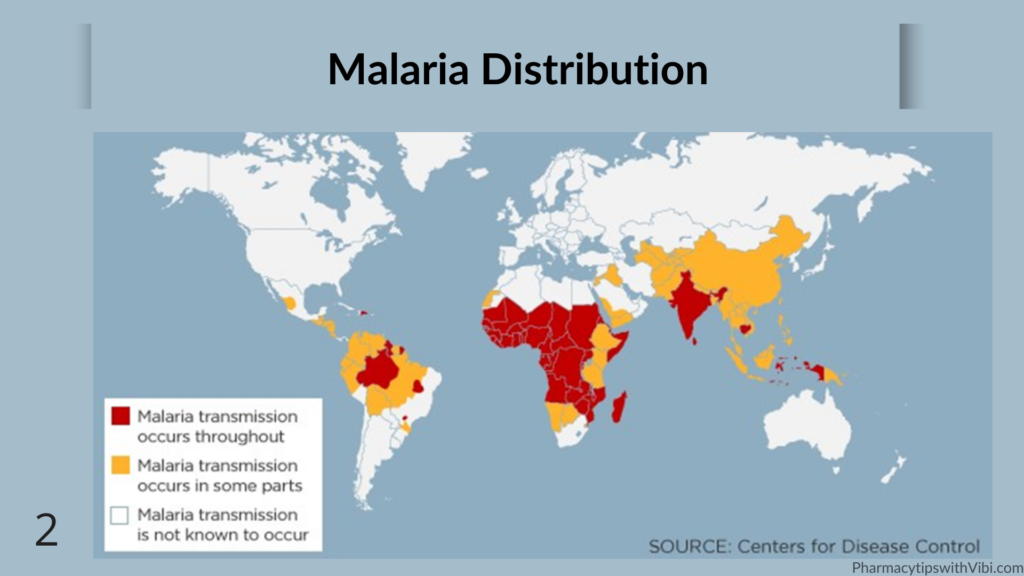

Malaria occurs mostly in tropical and subtropical areas of the world where people lack access to certain resources, such as housing with screens or medical facilities with proper testing and treatment capabilities. In many of the countries affected by malaria, it is a leading cause of illness and death. In areas with high transmission, the most vulnerable groups are young children, who have not developed immunity to malaria yet, and pregnant women, whose immunity has been altered by pregnancy. The costs of malaria—to individuals, families, communities, nations—are enormous (6).

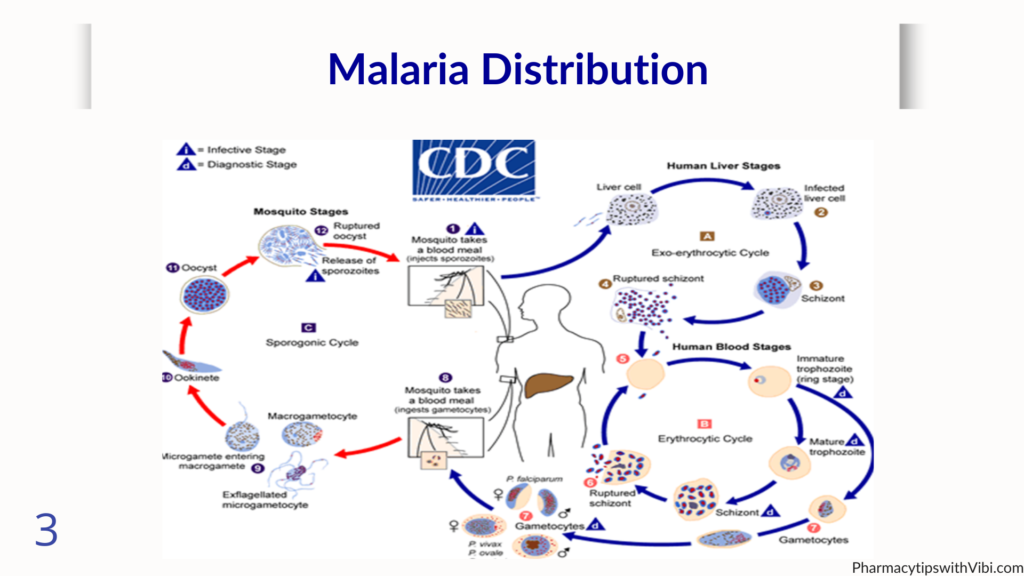

All Plasmodium species share a similar life cycle. It has two parts—in the first, the parasite infects a person (or a vertebrate host), and in the second, it is transmitted from the malaria patient (or infected vertebrate host) to another host by an insect vector. The vectors that transmit the five Plasmodium species naturally infecting humans are mosquitoes of the genus Anopheles. These mosquitoes also transmit other Plasmodium species parasitizing other mammals whereas transmission of Plasmodium infecting birds and reptiles depends on mosquitoes of other genera or other blood-sucking insects (7).

During a blood meal, a malaria-infected female Anopheles mosquito inoculates sporozoites into the human host. Sporozoites infect liver cells and mature into schizonts, which rupture and release merozoites. (Of note, in P. vivax and P. ovale a dormant stage [hypnozoites] can persist in the liver and cause relapses by invading the bloodstream weeks, or even years later.) After this initial replication in the liver (exo-erythrocytic schizogony), the parasites undergo asexual multiplication in the erythrocytes (erythrocytic schizogony). Merozoites infect red blood cells. The ring stage trophozoites mature into schizonts, which rupture releasing merozoites. Some parasites differentiate into sexual erythrocytic stages (gametocytes). Blood stage parasites are responsible for the clinical manifestations of the disease.

The gametocytes, male (microgametocytes) and female (macrogametocytes), are ingested by an Anopheles mosquito during a blood meal. The parasites’ multiplication in the mosquito is known as the sporogonic cycle. While in the mosquito’s stomach, the microgametes penetrate the macrogametes generating zygotes. The zygotes in turn become motile and elongated (ookinetes) which invade the midgut wall of the mosquito where they develop into oocysts. The oocysts grow, rupture, and release sporozoites, which make their way to the mosquito’s salivary glands. Inoculation of the sporozoites into a new human host perpetuates the malaria life cycle (8).

Most people get malaria when bitten by an infective mosquito carrying the malaria parasite. Only female Anopheles mosquitoes can spread malaria from one person to another. For the Anopheles mosquito to become infective, they must bite, or take a blood meal, from a person already infected with the malaria parasites.

About one week later, that same mosquito will bite the next person and subsequently inject the parasites via her saliva. And the cycle of infection continues.

In rare occasions, malaria can spread through; blood transfusions, organ transplant, sharing needles or syringes contaminated with malaria-infected blood, or congenitally, meaning from a mother to her unborn infant before or during delivery (9).

Understanding the life cycle and transmission of malaria parasites is paramount in addressing the global health burden posed by malaria. By comprehensively examining the types, characteristics, life cycle, and transmission modes of malaria parasites, we can develop more effective strategies to combat this debilitating disease and alleviate its impact on communities worldwide.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

- World Health Organization: WHO. Malaria. 24 Apr. 2019, www.who.int/health-topics/malaria#tab=tab_1.

- World Health Organization: WHO. Malaria. 4 Dec. 2023, www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/malaria

- Cosmos Magazine. “Why Mosquitoes Don’T Die of Malaria.” Cosmos, 4 May 2021, cosmosmagazine.com/health/medicine/why-mosquitoes-dont-die-of-malaria .

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Plasmodium | Malaria, Parasite and Apicomplexan.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 17 May 2024, www.britannica.com/science/Plasmodium-protozoan-genus.

- Stanford Health Care, 16 Jan. 2019, stanfordhealthcare.org/medical-conditions/primary-care/malaria.html.

- “Malaria’s Impact Worldwide.” Malaria, 1 Apr. 2024, www.cdc.gov/malaria/php/impact/index.html.

- Sato, Shigeharu. “Plasmodium—a Brief Introduction to the Parasites Causing Human Malaria and Their Basic Biology.” Journal of Physiological Anthropology, vol. 40, no. 1, Jan. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40101-020-00251-9.

- CDC, Malaria,www.cdc.gov/dpdx/malaria/index.html.

- “How Malaria Spreads.” Malaria, 12 Mar. 2024, www.cdc.gov/malaria/causes/index.html